Pololu Blog »

Posts tagged “pricing”

You are currently viewing a selection of posts from the Pololu Blog. You can also view all the posts.

Popular tags: community projects new products raspberry pi arduino more…

April 12, 2025 tariff update and new price change notification feature

As a small US-based electronics manufacturer, we have been contemplating tariffs a lot this year, especially over the last several weeks, when our mindset changed from primarily “let’s see what happens” to more of “this could be an existential threat and we need to act right away.” Like much of the world, we were shocked by the April 2 announcement of new, and high, US tariffs on seemingly everything from everywhere and the subsequent dramatic escalation of tariffs on China, which are up to 145%, or maybe 170% or 195% on some electronics components, as I write this on Saturday, April 12.

With the various pauses and extensions and exemptions that are announced almost daily, it might seem that the tariffs are just talk, but we have been getting hit by tariffs of 45-70% on electronics components for the past several months already. Often, these are for integrated circuits that we ordered months ago and that can ship from various countries, and we find out about the extra 70% cost only after we receive the parts. This summary from a recent Arrow Electronics order for some stepper motor driver ICs shows Arrow trying to get ahead of the tariff shocks and how high their estimate had gotten (I am not sure how they are calculating it, and it probably also changes day to day):

|

Order summary from an April 6 stepper motor driver chip order showing estimated tariff of 144%. |

|---|

We just finally mostly recovered from the pandemic-era chip shortages, and we don’t want to wait too long on reacting as we did then, when some of our key stock was quickly bought up and left us unable to manufacture some products for nearly two years. So, over the past week, we have gone through and assessed the pricing of all of the thousands of products we sell. Since most products have various quantity price breaks and pricing for our distributors, we updated tens of thousands of prices.

Our system is not made for this. When we release products, it’s usually one at a time and we carefully assess our costs and competing products to set what we expect to be good prices. If there are small cost increases over time, we usually absorb them, and if there is a big jump in some component cost, we can reassess and reprice the affected products individually. But here, we are dealing with the sudden, not precisely-specified, and unequal cost change of almost every component. So, the price changes that we have made over the past week have been much less carefully considered and more dependent on formulas based on costs and countries of origin and other data we have available.

Many of the “individual assessments” amounted to looking at prices our programs spit out and seeing if they seemed reasonable, and in many cases we just flagged the item for further review later and accepted the proposed prices or overrode to stick with our old prices. And, in some cases, we had to override to make the prices higher still based on knowing that a particular part was already constrained or getting higher tariffs.

This morning (again, Saturday, April 12) as I started writing this post, I saw news reports that semiconductor devices would be exempted from the latest extra hikes. Even if that applies to the kinds of integrated circuits we use, I think that means the 70% portion that we have already been paying is still staying in place. It’s also not clear to me if things like inductors, which we’re currently paying an extra 45% on are going to stay at 45% or going to 170% or what (basically all commodity inductors in the world come from China as far as I know). Even if they do get some exemptions or the tariffs are walked back more broadly, I suspect the 45% increase will be a new minimum for a while.

These new exemptions announced today should be good news for us, but I find myself feeling deflated as I contemplate more and more effort having to go into constantly repricing everything while looking at bills for extra thousands of dollars in tariffs almost daily. (This post is mostly about the work going into pricing for our customers, but there is also lots of decision making about what to buy now, such as do we get extra material now before prices go up more, or do we hold out hoping for them to go down and risk running out of components? Will the demand still be there for a product if it’s more expensive? And so on.)

Anyway, the point of this post is not to whine or wallow or complain, but rather to give our customers and partners some idea of how we are dealing with the tariffs. Price increases are not pleasant, and we are working on keeping them to a minimum and reducing prices again when we can. We are also quickly developing a new price change notification feature on our website so that you can be notified of price changes on any products you care about:

|

New price change notification feature. |

|---|

Because things are changing so quickly, we are rolling out this new website feature and I am announcing it before we have the notification email system implemented, so it might be a while before we can start sending out the notifications. I am thinking that until we have it all working and until things stabilize, this can also be a way for us to get feedback about which products might have been badly repriced and that we should prioritize for reassessment.

Please reach out and share your thoughts in the older established ways, too. Especially if you are a customer wondering about the future of some product, please let us know your concerns and we will do our best to give you whatever insight we might have and work with you on prices.

October 2022: still waiting for parts…

Wow, it’s been almost a year since my last update about how Pololu has been impacted by the global supply chain disruptions and chip shortages. And unfortunately, not much has improved. In today’s post, I will cover a few representative component stock histories and then go over other areas of our business that have been impacted and what we are doing to get through this situation.

Some parts on order since 2020 still have not shipped

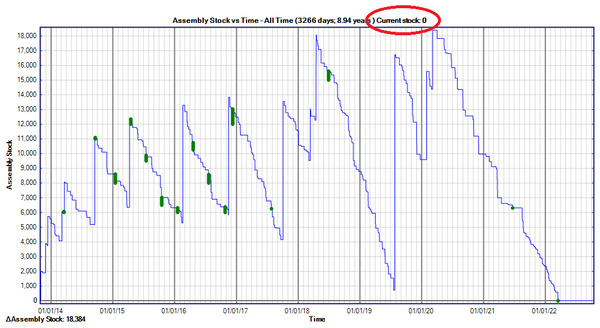

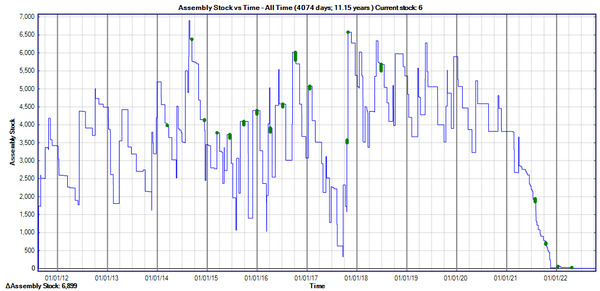

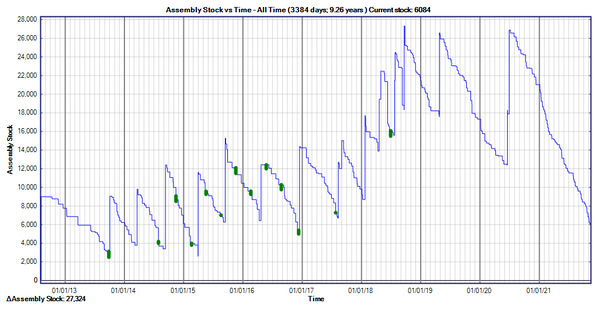

In the case of one important part I mentioned last year, we are still waiting for an order placed in late 2020 without having received anything since a partial shipment in March 2021! Here is what our internal stock chart looks like for that component:

|

When I wrote about this component in November of 2021, we still had 461 units in stock, and the manufacturer was giving me specific updates about where we were in line and how I could expect parts by Q1 2022 or maybe even by the end of 2021. Well, we are now getting close to the end of 2022, and they are not even giving me updates anymore on when I can expect these parts that I ordered in 2020! We have gone almost a year without being able to make or sell the products that use that chip.

Some parts arrived in 2021 and early 2022, but we are out again

That first example of still waiting for an order from 2020 is not typical. Unfortunately, we are seeing more and more of this pattern:

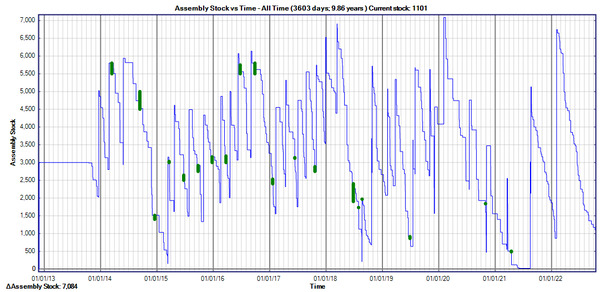

|

This is a component we ran out of over the summer of 2021, but we received some shipments in August of that year, and then more in early February of this year. But since then, nothing, and we are about to run out again despite our attempts to carefully ration the parts. It’s been over 14 months since I placed my oldest unfilled order for these parts, and the current expected ship date is February 2023.

Shifting demand clears out stock of alternative components

Another pattern we are seeing more of looks like this:

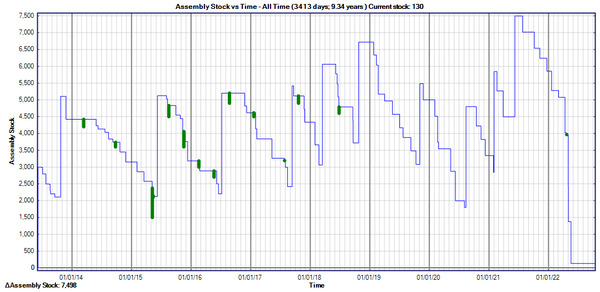

|

Here, we were in a pretty good stock situation at the beginning of the year on a component we didn’t use that many of. However, as we raised prices on other products or ran out of stock completely, our customers moved to some of our recommended alternatives and cleared us out of those, and hence the sudden dropoff of those parts in April of this year. The additional problem with components like these is that we did not have as many on order because our historical usage was not that high, so it might take an extra long time to get that back to decent stock levels.

New “supply outlook” feature

We commonly use the same components in several different products. One of the main ways we are dealing with the shortages is to substantially reduce our inventory of completed products so that we can be sure the components we do have are going toward products that are getting sold immediately.

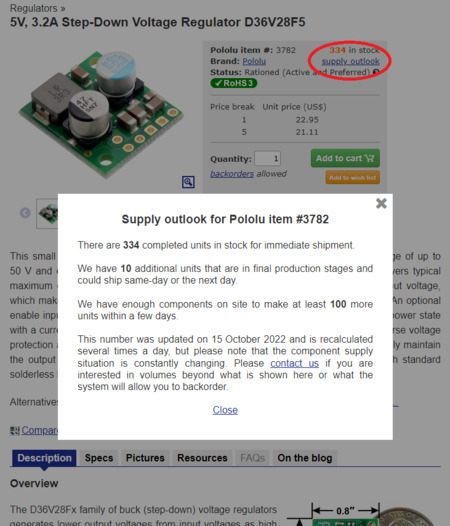

One big downside of reduced ready-to-sell inventory is that it’s difficult for customers to tell what is really, really unavailable because we’ve been out of parts for a year and what is actually available as soon as we make some more. To give you some automated guidance, we introduced a “supply outlook” feature to our website. Here is how that looks at the moment:

|

The calculations of what we can make are quite complicated given that we have thousands of different components going into thousands of different products, and the products (and the associated inventory) can be in various stages of production. Components stop being available once they are soldered onto a board, but that board might still go through many more processing steps before being ready and available for sale. The in stock and “in final production stages” quantities should be spot on, but we variously round down the “enough components” estimate to keep it conservative. The numbers can be outdated quickly since we are selling and making products all the time, but we regenerate those numbers several times a day to be as up-to-date as possible.

The supply outlook feature does not factor in components we have on order, though this year has proven that would be almost useless anyway (I’m not sure if I prefer the suppliers who give me no estimate of a ship date or those who have been saying “next week” for months). On our to-do list is to get more manual/human notes so that we can have updates like, “we are estimated to receive components in March 2024”.

I wish that last line was exaggeration. Unfortunately, I am getting more and more order confirmations with lead times of well over a year and estimated ship dates in late 2024. For parts I ordered early this year, we are approaching three-year lead time estimates for components.

Supply chain issues impact other aspects of business

Although the chip shortages are the most nerve-wracking aspect of the current environment, other aspects of our business are also affected by the supply chain problems, and it’s getting more and more uncomfortable.

- Waiting more than 9 months for commercial air conditioners - One literal example is the air conditioners in our building. We have over fifty of them, and dozens of them are over twenty years old, meaning they are inefficient and reaching the end of their useful lives. We have had several on order since the beginning of the year, and at this point we are hoping that maybe they will arrive by the end of this year. Fortunately, we made it through the summer, but several units did die recently, and it’s not clear that we can even have them replaced by next summer.

|

Old ACs on Pololu building roof, waiting for replacement. Las Vegas Strip in the background. |

|---|

- Waiting more than 6 months for window film - We started applying special solar-blocking films to our windows to help reduce the energy use by the ACs. That project started in late spring, and although part of it got done over the summer, most of it has been delayed by at least six months waiting for more of the film to get manufactured.

|

Pololu window tinting, July 2022. |

|---|

- 6-12 month lead time on compressors and nitrogen generators - We ordered a nitrogen-generation system earlier this year, and lead times on that are in the ballpark of a year as well. There are several components to the system and we get billed for them as they arrive, so I don’t think the manufacturer is holding back on any of them while waiting for the others. One component is a fairly standard (though nice) air compressor that I am expecting to use for the rest of manufacturing as our existing ones are getting kind of old. It’s scary to think some of our production or equipment could be out of commission for a year waiting for machines or components that normally are available within a few weeks.

Outlook

We have been very fortunate at Pololu because we have a broad range of products and do our own design and production, so we have been able to adjust what we make based on what components are available. I don’t understand how more small manufacturers are not going out of business, though I am anecdotally starting to hear more about companies facing financial difficulties. Contract manufacturers in particular have it tough when they have to pay for the components they can get while waiting forever for the last few components and not getting paid until they can complete the final product.

My main hope is that just as we could not see how bad the shortages would be, we cannot see how close we are to the end. If it took two years to get a part that shipped today, it might be reasonable to estimate it will take two years to get a part we order now, or even to tack on an extra year for good measure, but eventually things will be better. I expect inventories everywhere are building up (ours are, just not of the last few critical parts!), and the coming global recession that seems to be forecasted from all sides (e.g. by the IPC) could accelerate chip manufacturers finally catching up to the extra demand from the last few years.

Since we are a small business, broader economic downturns can sometimes work in our favor. Our customer base is such a tiny portion of the world, and some of them could do well even if on average the global economy does not. If the slowdown leads to parts we need becoming available sooner, that might overall be better for us. Some of our best supplier relationships came out of the 2008 downturn, when companies started caring about our business after losing some of their bigger customers. We also got a good deal on renting part of the building we are in after it sat vacant for a couple of years, and that served us especially well as we gradually expanded to the whole building over the past ten years.

It’s unsettling that after two years of parts shortages, it does not seem to be getting any better. The situation might even be worse than it was a year ago, but we won’t really know until we are out of it and things are actually good again. I know it has been difficult for our customers, especially those who built our products into their own products or curricula and are counting on us to keep their operations moving. Please know that we are working very hard to keep our stock and production levels up with the minimal possible disruptions, and thank you very much for your continued business and support.

November 2021 operations update: supply chain disruptions, price increases, and component rationing

Nearly two years of operations under the COVID-19 pandemic are behind us. Like many other businesses around the world, our biggest challenges have moved from direct health and safety concerns to secondary disruptions, most notably the supply chain issues and the global chip shortage that has been making news and shutting down factories since last year. Initially, we were relatively isolated from the shortages because we had maintained a high inventory, often stocking a year or more of critical components. However, as the disruptions dragged on, our reserves were depleted, and we have had to resort to increasingly drastic measures to keep operating at all.

I apologize to our customers who are frustrated by our worsening response times, price increases, and unavailability of products. I hope showing you some of what we are dealing with will make it easier to understand.

Here is a screenshot from our internal system showing the inventory history of a relatively unremarkable component (a small MOSFET) that we have been using for almost ten years now:

|

Inventory history for a component with shortages in 2021. |

|---|

The stock history is representative for a typical component that we gradually put into more product designs so that the rate of usage keeps increasing and the amount of stock we keep on hand gradually increases, too. Usage of this part ramped up in 2018, to around 35 thousand pieces per year. We last received some shipments in mid-2020 that put us in a seemingly-secure place, but the situation became less comfortable as we got into 2021, and the past several months have been downright alarming since we might only have enough parts for two more months, while the estimated shipment dates for my orders are well into 2022. And this is with us putting the brakes on parts usage!

Rationing

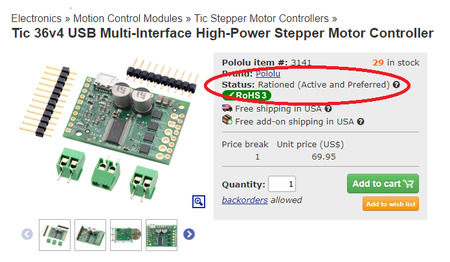

Slowing down component consumption is really not fun since our main options are just not making any of a product at all (sometimes we are forced into that option anyway once we run out of parts) or raising prices. Higher prices can make it confusing for customers to select among alternatives since we expect the more expensive product to generally be the better one. To help communicate that some products’ prices and availability are temporarily distorted, we added several rationing-related entries to our list of product status designations. You can see the status of each product along with stock and pricing information:

|

We initially focused on reducing volume discounts, and building the rationing designations into our system let us automatically exclude rationed items from sales and other special promotions. It has been almost six months since we started officially designating products as rationed, and unfortunately, what we expected to be a temporary measure for a few select items has gradually affected more and more products as component shipments keep getting delayed.

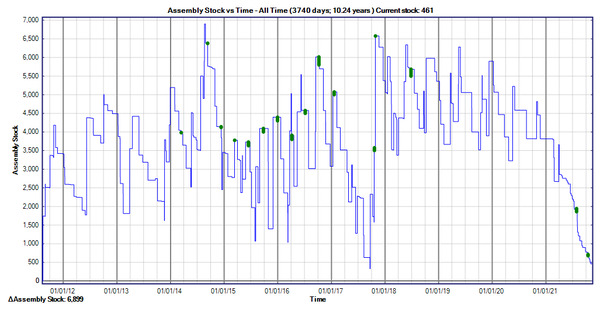

Here is the inventory history for another component, a more expensive and specialized part than the previous one:

|

10-year inventory history for a component being rationed in 2021. |

|---|

There were already some supply issues with the part in 2017 that led us to keep slightly higher inventory of that component, and you can see the change in the pattern as we ramped up our rationing efforts. We buy the part on reels of 1,000 pieces, so the upward jumps in the graph are multiples of a thousand, and we used to use up fairly high quantities in each manufacturing run, so the downward jumps were fairly sizable, too. For instance, we might make five hundred of a product at a time and just put it all in stock on the website and not make more for a couple of months. Starting in the second quarter of this year, you can see how the inventory graph is a lot smoother as we made much smaller production runs to preserve flexibility in which products to use the components.

This strategy does help us maximize the usage of the parts we have on hand, but it comes with many costs. Production is less efficient since the machine setup is the same whether we are making twenty units of a product or a thousand units. We also have much more internal scrutinizing, planning, and checking of which products to make since accidentally making the wrong product is a much bigger problem than it used to be—it could now mean prolonged inability to make a different, otherwise unrelated product. It’s also more difficult on customers who do want to buy in bigger volumes since we used to have more stock available on our website, and customers could just order. Now, when we show 29 of a motor controller in stock and a customer needs 50, they have to talk to us about how soon we can make the additional 21. This also strains our support staff resources and reduces the service quality for all customers. And the sad thing is that we are doing a lot more work to produce and sell fewer products.

What inventory do we do have?

You might be surprised to hear that our total inventory is actually at an all-time high. And apparently, that is fairly common, even among the biggest companies, including the main electronics distributors. When I was talking to my Arrow Electronics rep last month, he said his warehouse is full. I asked of what, and he said he didn’t know, but apparently not the parts he needs.

|

I spend a lot of time trying to understand what we do have. We have thousands of unique components, and on average we have thousands of each one, so we have many millions of components to keep track of. Most products use many different components, and most components get used in many different products. If we are missing one part out of fifty to make a product, we can’t make the product. And usage rates for the same component are different in different products; what are we supposed to do when we have five thousand left of a component that we use in a $5 product that used to sell thousands of units a month and in a $100 product that sells hundreds of units a month, and the earliest estimated delivery of more components is eight months out? So far, we have mostly raised the prices on the $5 product, sometimes very substantially, while not changing the price on the $100 product, and that lets us keep some finished products available to offer.

There are more and more components that have been on order for over a year now, and meanwhile estimated ship dates for new orders are well into 2023 (not 2022!). It’s a scary time to be an electronics manufacturer.

Other cost increases

As I mentioned, we are going through a lot more effort to make fewer completed products, and that contributes to increased costs and higher prices independent of what we are doing with rationing. On top of that, prices for most of the components we have been using for a long time have risen substantially, even as our order volumes increase. Most increases have been in the 10% to 20% range, but several are 50% or more.

Then there are parts that we now buy in smaller quantities from catalog distributors like Digi-Key and Mouser (when we find stock there), and those prices can be several times higher. Some parts I bought a year ago for twelve cents each in quantities of fifty thousand are now costing 25 cents each in those bigger volumes, and if I order just a few hundred or a few thousand, they can cost a dollar each. If we just need one of those on a product we sell for $100, it’s not that big of a deal, but if there are three of those components on a product that used to cost $5, the price is going to have to go up, sometimes dramatically.

|

Non-electronics component and material costs are also going up, though those have generally been in the more modest 5% to 20% range, but shipping costs are up a lot, so that disproportionately affects heavier and bulkier items. We have had to reprice some of our stepper motors primarily because of the shipping costs to get them here, while we have thus far been able to avoid raising costs on our micro metal gearmotors (though volume discounts are smaller than they used to be). Most of our products involve at least some processing in the US, but we are able to ship some items directly from our China warehouse to other countries to reduce the impact of shipping costs and the tariffs on many products coming into the US from China.

Broader problems and delays

|

The broader supply chain issues are a problem, too, even though it’s not as bad as with the chip shortages. Most of our mechanical parts, from injection molded plastic parts to motors and servos, come from China, and we are more directly involved in getting them shipped here (unlike the electronics parts, which are also mostly made overseas but which we buy from American distributors who deal with getting the parts into the US). Fortunately, most of our components are small and light so we ship a lot by air anyway, but we do ship heavier and bulkier items by boat and have had our share of days looking at all the ships waiting off the coast of California and wondering when ours would finally get to dock. It seems like regular delays by various carriers like FedEx and UPS are also getting worse, and we have now had at least a couple of instances where really important parts we were waiting months for made it to the US or even to Nevada and then got lost.

I have been writing mostly about components and how it affects electronics we manufacture, which is most of our business, but the other small manufacturers whose products we resell are in the same environment, and so we are seeing price increases and extended unavailability of products from them, too.

Delivery delays and other problems are affecting our shipments to our customers, too. Unfortunately, we are again mostly at the mercy of the large shipping companies and the general situation that has led to reduced service levels around the world. Many of the providers have suspended guarantees of delivery times or extended the times they say delivery will take. We have recently added UPS to our standard shipping offerings during checkout, so our customers at least have some more options in case one service is particularly bad in their area.

When will it get better?

As I wrote a few years ago, we buy our electronics components through major authorized distributors, and we have so far not had to resort to going to secondary sellers and brokers (with the associated risks of ending up with counterfeit parts). From my talking to manufacturers’ representatives, my impression is that the semiconductor companies are just genuinely facing a combination of increased demand and reduced capacity as the pandemic interfered with their operations that are spread throughout the world. For example, ST was telling me about one motor driver that gets the silicon processed in Italy, then tested (still in silicon wafer form) in Singapore, and then chopped up and packaged in Malaysia. In this one instance, the silicon is done, and as operations resume in Malaysia, they should be able to get me some of the parts by the end of the year. But for other parts from the same company, such as microcontrollers, they don’t even have enough allocated to my general western North America region to meaningfully talk about where in the queue we are.

When I first heard predictions in early 2021 that the chip shortages would drag on through the end of the year, I didn’t really believe it. It’s increasingly clear that those predictions were right, but at least 2022 is not that far away anymore! And while we do have many orders with expected ship dates two years out (late 2023), we also have several with expected ship dates in early 2022 (and some parts have been trickling in, so it’s not as if we were completely choked off on all supply).

As we approach the holiday season when we traditionally have our biggest sale, we are assessing which products we can make and possibly discount. We have a few new releases this year that we are very excited about, but new products are especially difficult to ramp up, especially if they use new components we didn’t already have on order a year ago.

|

|

Thank you for your continued business and support

Despite the various challenges presented by the evolving pandemic and associated disruptions, we have generally been able to keep operating relatively smoothly this year. I know there are many small businesses of all types struggling or even having to shut down completely, and I am very grateful that we have avoided such extreme scenarios. Thank you to all of the employees at Pololu for so reliably keeping everything running, and thank you to all of our customers for your continued business. I wish everyone a safe and happy conclusion to the year and look forward to things improving on all fronts in 2022.

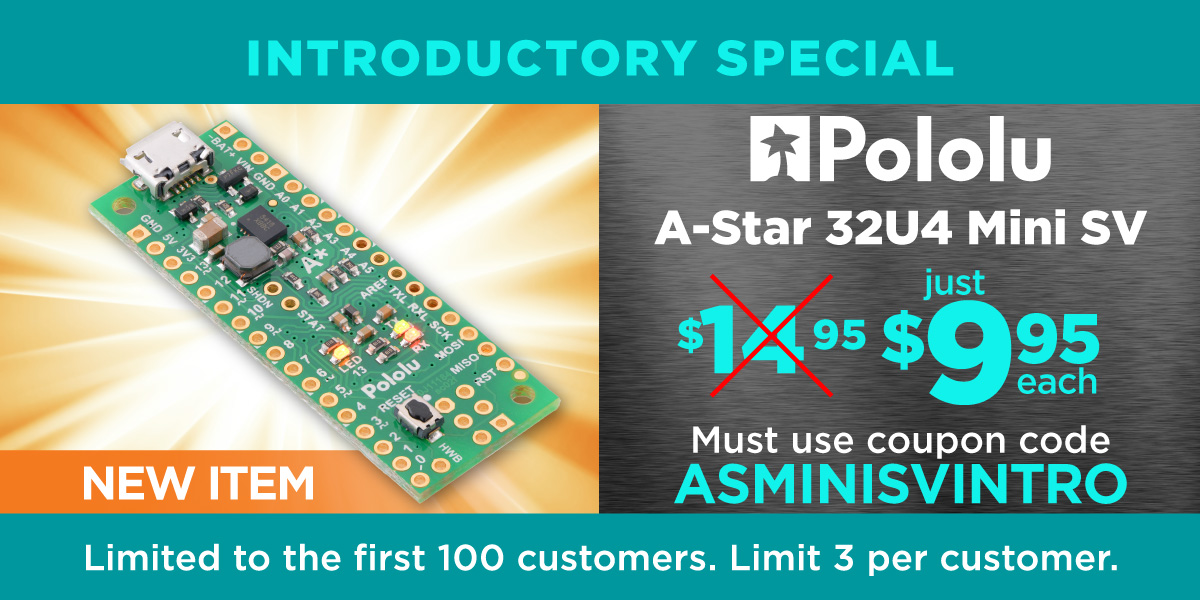

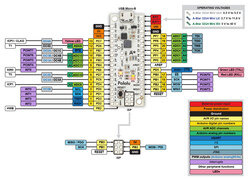

Updated product: A-Star 32U4 Mini SV

|

A-Star 32U4 Mini pinout diagram. |

|---|

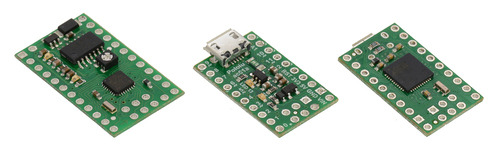

I think of our new A-Star 32U4 Mini SV as more of an update than a genuinely new product. For those of you not already familiar with our A-Star 32U4 Minis, they are a series of ATmega32U4-based, USB-programmable controllers with integrated switching regulators that offer operating voltage ranges not available on typical Arduino-compatible products; the “SV” variant features a step-down converter that enables efficient operation with inputs as high as 40 V. The slight PCB update for this latest product was done primarily for manufacturing reasons (e.g. reset button footprint change, addition of a test point, and switching to an ENIG finish that has worked better for us for double-sided assembly), but I figured that while we were updating all our internal records for the new PCB, we might as well also upgrade the regulator.

There’s a difficulty to making small improvements to products when we have hundreds of distributors around the world since even if we clear out our inventory of older versions before shipping newer units, we cannot control the inventory at distributors’ warehouses. We’re all usually tolerant of products being a little better than advertised, but when we try out a product, and then buy another one, and it ends up being worse than the one we already had, it just doesn’t feel right. (That’s one reason we sometimes do not reveal exact components we use, to avoid over-specifying some aspect of a product that we feel is not that important and that we do not want to commit to.) Once the regulator was different (and better!) enough to merit changing the product specifications, we needed to change the product number, and hence we have a new product.

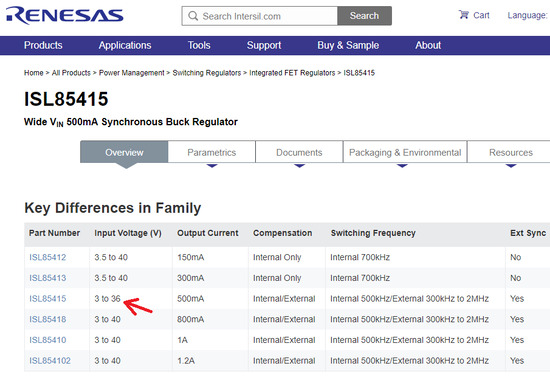

The regulator change is from the ISL85415 to the ISL85418, both made by Renesas (which acquired Intersil). The ISL85415 was the first of a great regulator family by Intersil, and they expanded the family with several pin-compatible versions with various current specifications. These new parts could also operate to 40 V instead of the 36 V of the original ISL85415, but even as various aspects of the datasheets got updated, the maximum voltage rating on the ISL85415 in particular did not.

|

Renesas website screen capture showing ISL85415 is only part in its family with 36 V maximum input. |

|---|

I asked our Intersil contact about why only the ISL85415 wasn’t rated to 40 V. It sounded like it was getting made on the same process as the other parts, and that the higher voltage rating of the later parts in the family was more the result of better characterization (and thus confidence) in the process than in any modifications to the process. In other words, new ISL85415 parts can probably do 40 V just like the other parts, and the older ISL85415 parts probably the same; they just weren’t confident about calling them 40 V parts then. But who knows what the inside story is. Maybe they did tweak their recipes a bit, and once they had parts out in the world with the 36 V spec, they didn’t want to change it without changing the part number, just like we couldn’t just keep our old A-Star part number and also talk about the higher maximum input voltage.

|

A-Star 32U4 Mini ULV, LV, and SV. |

|---|

In case you’re wondering why we didn’t just put the even better ISL85410 or ISL854102 with 1.0 A and 1.2 A outputs on the new board, it’s because the performance limit moved more to the inductor, and even if the better regulator chip takes up the same space, we would need a bigger inductor to take advantage of that. And the A-Star Minis are pretty packed designs, so there’s not much room for a bigger inductor.

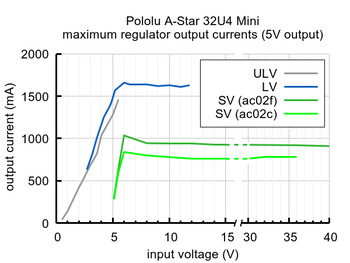

So, to make a long story short, the main new feature of the updated A-Star 32U4 Mini SV is that it can now take up to 40 V input and give you up to 800 mA to work with. This chart shows you what the new regulator (in darker green) can do compared to the older one (lighter green) on the A-Star Mini. It looks like the old one already provided well over its 500 mA specification.

|

Typical maximum output current of the regulators on the A-Star 32U4 Mini boards. |

|---|

To make this new product a little more exciting, we reassessed our costs and cut some of our margins in keeping with our push this year to be more competitive in our manufacturing. We have reduced the unit price from $19.95 to $14.95. And as usual for our new product releases this year, we’re offering an extra introductory discount: use coupon code ASMINISVINTRO to get up to three units for just $9.95. (Click to add the coupon code to your cart.) Our promotion banner shows the usual limit for the first 100 coupon uses, but since we’re also having our Arduino Day sale, we’re removing that restriction for the duration of the sale. If we run out of stock during the sale, you can still backorder with the discount, and we should be able to catch up with production within a few days.

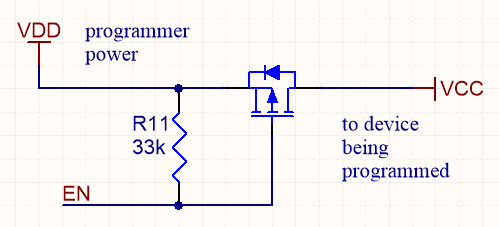

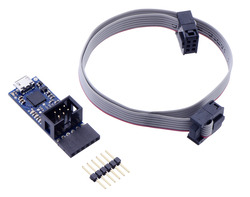

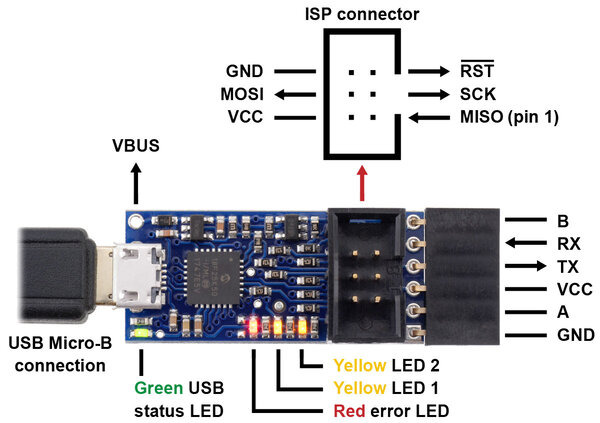

New product: Pololu USB AVR Programmer v2.1

Our new programmer, the Pololu USB AVR Programmer v2.1, was supposed to be a minor update to our existing programmer, coming right after the A-Star 328PB Micro that we released last month, with the main point of excitement being the Las Vegas-inspired $7.77 price. But as we were testing the combination of the programmer with the A-Star, we were getting brown-out resets on the programmer when it powered the A-Star. The relevant part of the circuit was just a P-channel MOSFET that connected the programmer’s own logic voltage (which we call VDD) to the VCC pin of the ISP connector:

|

MOSFET-based target VCC power control used on Pololu USB AVR Programmer v2. |

|---|

The problem was caused by the MOSFET turning on too well (quickly and with low resistance), causing the logic voltage on the programmer to drop if the VCC of the target device had more than a few µF of discharged capacitance on it. The bigger the capacitance on VCC, the bigger the voltage drop on VDD, until eventually the drop was big enough to trigger the brown-out reset protection on the programmer’s microcontroller. We tried various firmware tricks with our existing hardware, such as turning on the MOSFET for very short pulses to gradually charge up the target device’s VCC capacitance, but none of them worked reliably enough. So in the end, we decided to redo our PCB and put in a dedicated high-side power switch with a controlled slew rate. The new programmer can now power target boards with up to about 33 µF on their logic supplies.

These are the two other improvements we made to the new v2.1 programmer over the older v2 programmer:

|

- Plugging a v2 programmer into a 3pi robot could cause one of the motors to briefly run at full speed because the programmer’s circuitry for measuring VCC could inadvertently pull up one of the 3pi’s programming pins (which doubles as a motor driver input) before the GND connection was established. The v2.1 programmer has improved circuitry for measuring VCC which limits the duty cycle of this effect to about 0.2%, so the motor won’t move (but it might make a 25 Hz clicking sound).

- The v2 programmer would typically brown-out if a 5 V signal was applied to its RST pin while it was operating at 3.3 V. The v2.1 programmer does not have this problem.

The v2.1 programmer is otherwise identical to the v2 programmer, which means it’s a USB AVR microcontroller programmer that can program targets at 3.3 V and 5 V and offers an extra UART-type TTL serial port (like the popular FTDI USB-to-serial adapters) that can be super handy for debugging, bootloading, or even general connection of your project to a USB port.

|

Pololu USB AVR Programmer v2.1, labeled top view. |

|---|

The v2 programmer was already a good deal at under $12, but at $7.77, and with free shipping in the USA, we hope to make AVR development extremely accessible. The manufacturing improvements and other cost reduction initiatives I have been blogging about this year help us make this offer without losing money on it, but I am not expecting to be making money directly off of the programmers, either. My goal is to give you the best value in a basic tool you will use over and over as you build your own projects, with the hope that that will help you keep Pololu in mind the next time you need some electronics or robotics parts.

And, as usual for our new product releases this year, we’re offering an extra introductory discount: the first 100 customers to use coupon code AVRPROGINTRO get that already great $7.77 price dropped to $5.55 (limit 2 per customer). (Click to add the coupon code to your cart.)

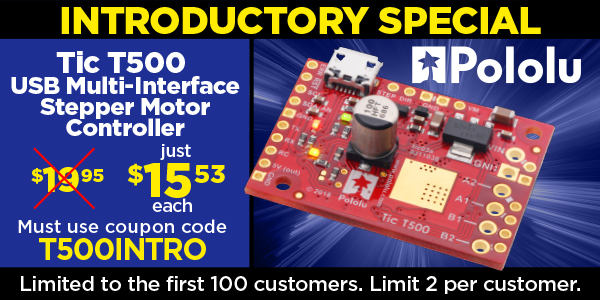

New product: Tic T500 USB Multi-Interface Stepper Motor Controller

Our Tic stepper motor controllers are pretty awesome, and the new Tic T500 we released today should make stepper motors even more accessible for your next project. This latest version features a broad 4.5 V to 35 V operating range that covers everything from small 2-cell lithium battery packs up to 24 V batteries or power supplies while costing just $20 in single-piece quantities. This video gives you a quick overview of what the Tic stepper motor controllers offer:

The Tics make basic speed or position control of a stepper motor easy, with support for six high-level control interfaces:

- USB for direct connection to a computer

- TTL serial operating at 5 V for use with a microcontroller

- I²C for use with a microcontroller

- RC hobby servo pulses for use in an RC system

- Analog voltage for use with a potentiometer or analog joystick

- Quadrature encoder input for use with a rotary encoder dial, allowing full rotation without limits (not for position feedback)

The Tic T500 is available with connectors soldered in or without connectors soldered in. Here is a handy comparison chart with all three Tic stepper motor controllers:

Tic T500 |

Tic T834 |

Tic T825 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating voltage range: | 4.5 V to 35 V(1) | 2.5 V to 10.8 V | 8.5 V to 45 V(1) |

| Max current per phase (no additional cooling): |

1.5 A | 1.5 A | 1.5 A |

| Microstep resolutions: | full half 1/4 1/8 |

full half 1/4 1/8 1/16 1/32 |

full half 1/4 1/8 1/16 1/32 |

| Automatic decay selection: |  |

||

| Price (connectors not soldered): | $29.95 | $39.95 | $39.95 |

| Price (connectors soldered): | $31.95 | $41.95 | $41.95 |

1 See product pages and user’s guide for operating voltage limitations.

Basically, the new T500 does not offer the finer microstep resolutions of the T834 and T825, and the T834 supports very low operating voltages while the T825 supports higher operating voltages.

For those of you interested in more of the details of the stepper motor driver, the Tic T500 uses the new MP6500 from MPS, which we also offer on some low-cost MP6500 breakout boards with analog (small trimmer potentiometer) and digital (via PWM) current limit setting options.

In keeping with the tradition we started this year, we are offering an extra discount for the first customers, to help share in our celebration of releasing a new product. The first hundred customers to use coupon code T500INTRO can get up to two units for just $15.53! (Click to add the coupon code to your cart.) And we’ll even cover the shipping in the US! Note that this introductory offer applies only to the units without connectors soldered in.

Purchasing electronics components in America

|

I am a little proud (but mostly embarrassed) that I still do basically all of the electronics component purchasing for Pololu. Today I am writing about buying components because their prices have a huge impact on the end price of our products, especially when we work to cut down other costs as I have been discussing lately. Buying parts when trying to compete globally is more frustrating than you might think, and I hope that writing this will help trigger some conversations that will help us do better and also encourage component manufacturers and distributors to better support small electronics manufacturers in the United States.

I buy almost all of the electronic components that go into our products from suppliers in the United States. That includes integrated circuits, discrete semiconductor products like transistors and diodes, resistors, capacitors, inductors, and so on. The only parts I do not buy in America are components like connectors and electromechanical devices like switches and buzzers. This post is mostly about buying components in the US from US suppliers, but I will briefly touch on the non-US components to provide some background and comparison.

|

There are two main reasons for those non-US components: they are much cheaper than similar parts in the US and we can evaluate that they are good enough. That second reason is important because counterfeits and fake parts are a big problem in the electronics industry. We can look at something like a 0.1" male header or an electromagnetic buzzer and see basically what it is. Once we can be confident that a component or supplier is good enough for the level of performance and reliability we need from our products, we can look at prices to see whether it’s worth the extra hassle (and that amount of hassle keeps going down) to get the components overseas, which pretty much means China (and Taiwan, in case that distinction is meaningful). And that price difference can be huge. When I started getting connectors directly from Taiwan over ten years ago, the price difference was approaching a factor of ten, meaning that for around a thousand dollars I could buy what would cost me ten thousand domestically. Some of the price differences seem to be getting smaller, but the components still seem to be easily three to five times cheaper in China. Early on (around 2005), local salespeople would ask me what prices I was getting in China, thinking they had some better deal or connection than I knew of; nowadays, they don’t even ask or try to compete.

With all the other component types, even for the most basic parts like resistors and capacitors, we are not really qualified to evaluate them, and I would not want to be responsible for doing quality control for millions of units even if we could analyze one particular instance of a resistor or capacitor and conclude that it is good enough. So, I only buy components from reputable brands through their authorized distributors, which means I buy basically all our components through American companies (with one exception I’ll get to soon that almost doesn’t feel like an exception, anyway). Those companies also tend to be the biggest electronic parts distributors in the world.

I still buy some components from the catalog-type sources that are probably familiar even to most students and hobbyists, like Digi-Key, Mouser, and Newark. Once upon a time, these companies printed large catalogs that were the best way to find out what kinds of components even existed (especially when I was growing up in Hawaii). Digi-Key stopped printing catalogs a few years ago; Newark apparently still does. In any case, these kinds of sources now have good online resources for finding parts, they tend to have a lot of parts in stock, and they are set up for small quantities, which is why they are great resources for individuals, too. Usually, it’s very easy to buy components from these sources, and I rarely interact with anyone when I do since I usually just place the orders through the web sites at their listed prices.

|

However, the prices usually are not the best at those most convenient sources, especially when my minimum quantities tend to be full reels with thousands of parts rather than a few individual parts. So for most of my electronics purchasing, I go with big distributors like Arrow, Avnet, and Future Electronics. These companies have local offices (though for Las Vegas, “local” tends to mean in Phoenix, Arizona or somewhere in Southern California) that have salespeople that I can talk to that can help me get lower prices. Future Electronics, being a Canadian company, is the exception that I mentioned earlier; but, working with them is basically the same as working with Avnet or Arrow since they have the local staff and things like a distribution center near Memphis, Tennessee (here is a video about it).

Back when I was a student and before I started Pololu, I thought electronics distributors just bought components from manufacturers and then sold them with some markup on their cost. I think some of that did happen and still happens today, but it’s less common and less practical now because there are so many different, specialized components that they cannot all just be sitting in stock somewhere, waiting for the unlikely scenario that someone would come along and buy them. When I buy from distributors like Digi-Key and Mouser, I am almost always buying something they have in stock; when I buy from Arrow and Future, it’s almost never something they have in stock (or it’s something they have in stock because they had good reason to expect me to order).

But there was a much bigger misconception in my naive view than just the timing of when a distributor bought some parts relative to when the end customer ordered them. The major thing I learned in the early years of running Pololu is that component manufacturers charge the distributors different prices for the same components, based on the end customer! In some ways, that’s frustrating because it means I have to do a lot more work to get a good price. I have to convince each distributor and each manufacturer to give me a good price, and sometimes I have to do that with each component. It can also be a good thing in that if I do establish a good relationship with some manufacturer and distributor, the hassle per part goes down over time as they get to know our business and what factors are important to us. And some of them probably do give me a globally competitive price sometimes.

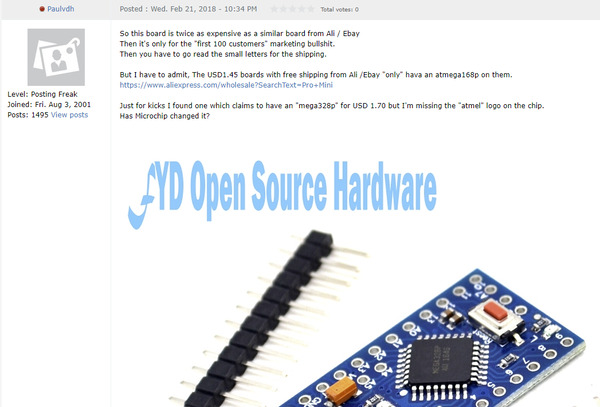

The difficulty, and what prompted me to write this post, is with those manufacturers that do not. (That or counterfeits, which is sometimes the explanation or excuse I get back from manufacturer’s representatives.) Well, the really specific thing that led me to write this post is the AVR Freaks thread about my last post, in which I introduced our new A-Star 328PB Micro:

|

AVR Freaks post about A-Star 328PB Micro announcement, the motivation for this blog post. |

|---|

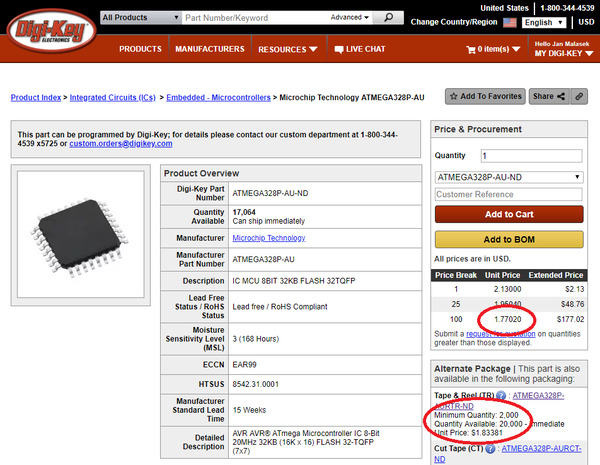

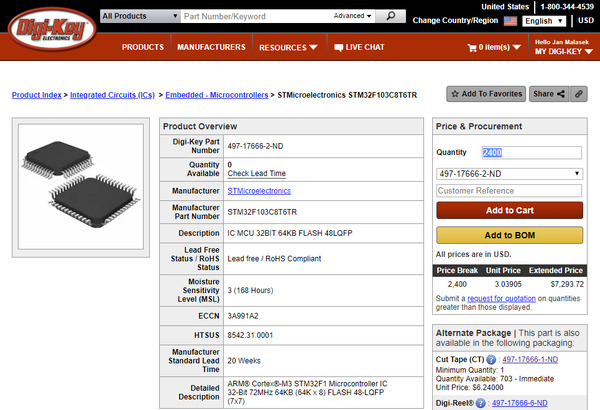

The poster mentions a board similar to Pololu’s with an ATmega328P for $1.70 (and wonders about the chip authenticity). I went to look at the part price on Digi-Key, and this is what I saw:

|

Screenshot of Digi-Key price for ATmega328P with prices highlighted, retrieved 25 February 2018. |

|---|

I have highlighted the relevant fields, which are the lowest prices: $1.77 each at 100 pieces, and alternately, on a reel of 2000 pieces for $1.83. 100 pieces is kind of low for a highest price break. A long time ago, I tried out the higher volume quote request option that is suggested under the 100-piece price, and after some back-and-forth, Digi-Key gave me an official volume quote for higher quantities with the exact same price as at the 100-piece break:

|

Excerpt from quantity price quote from Digi-Key (from around 2010) |

|---|

I tried it a few more times with some other parts, but it was basically the same result every time, so I have not tried special pricing with Digi-Key since. That was close to ten years ago, so maybe it’s different now, and maybe it would be different if I had asked for 10k or 100k pieces.

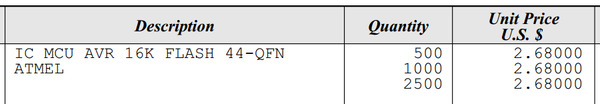

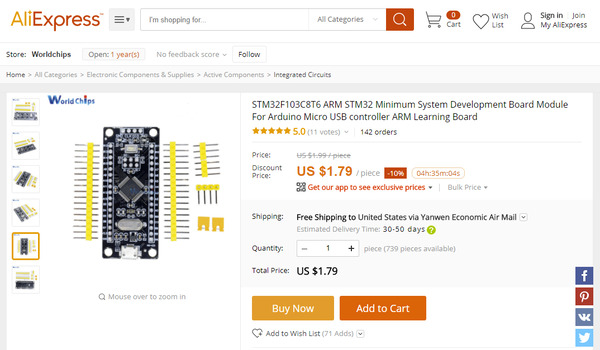

Back to the original point: you can get the whole assembled board from China, in single-piece quantities, for less than the price of just the one component, even in volume quantities. And this Atmel/Microchip example is far from atypical or anywhere near the worst case. Here is an AliExpress listing for a small development board for the STM32F103C8T6 microcontroller:

|

AliExpress listing for an STM32F103 development board for $1.79 including shipping, captured 25 February 2018. |

|---|

In this case, Digi-Key has prices listed for higher quantities than in the earlier example, and the 2400-piece reel has the best unit price of $3.04:

|

Screenshot of Digi-Key price for STM32F103C8T6, retrieved 25 February 2018. |

|---|

I have been working on pricing for similar STM32 parts, and even at twenty thousand pieces (not through Digi-Key), they are not getting to the prices of just one of these complete boards, with double-sided assembly and a bunch of additional components (and free shipping!—though that is some separate scam that I do not blame the electronics component manufacturers and distributors for). Something clearly doesn’t add up, right?

|

As I mentioned earlier, some manufacturers will say the parts in the cheap boards from China are counterfeits. I believe that is the explanation in some cases, and we have our share of frustrations with knock-offs and counterfeits of our own products. But I had one experience around five years ago that makes me very skeptical that that is anywhere near the whole story. One of our more successful early products, at least by number of units sold, was a basic carrier for Allegro’s A4988 stepper motor driver. I remember being frustrated because Allegro seemed to have some deal in place with Digi-Key that gave them the best prices (and unlike the examples above, Digi-Key did have volume breaks up to many tens of thousands on that part). Digi-Key has been getting better on prices, but still, paying “Digi-Key prices” seemed like an insult when I was buying tens of thousands of these parts at a time.

It became more of a problem when the knock-offs of our boards started appearing on eBay and other sites for basically the same prices as just our component costs. I kept trying to get my suppliers to help me with my prices until I got the parts from Asia via Future Electronics. They assured me these were genuine parts through their global partners or subsidiaries, and they could do that for me because they were not authorized distributors for Allegro in the United States. So, that alone was a good indication that these parts were out there, through reputable sources, at lower prices than I could get in the US. But the conclusion to this story gets better: someone who could do something about it at Allegro finally got word that I was getting these parts elsewhere (they noticed the sales abruptly went away, and they wanted to see my invoices from other vendors) and reduced my authorized price, through Arrow, to almost half of what it had been.

This was over the course of maybe two years, and while it did help and we lowered our prices, I believe we missed out on a lot of potential sales because it took so long to get the prices down. The sad thing is that there are probably many more missed opportunities, not even just for Pololu, because of how components get priced in the US. The manufacturers seem more willing to cut prices after demand is proven and they start losing sales rather than up front to make the sales happen in the first place. And to be clear, I am not talking about small quantities like broken reels and cut tape that require extra handling and processing. I also understand that these modern 32-bit microcontrollers like the STM32 are such amazing achievements that it seems really unappreciative to complain about one costing $2. It’s just that when the same parts are costing one dollar somewhere else, we need to figure out how to get that price if we want to be globally competitive with our products.

Since I know many of you are also interested in open-source hardware, I should mention the ramifications component pricing has for openness with our designs. One of the factors that goes into how much information we release is how good I think our component price is. It’s easier to share key components that we use if I think we can keep making our products competitively.

Back to some of the comments that led me to start writing on this topic. I hope I have shown you a different kind of behind-the-scenes view than just the machines that go into making our products. Some of that “twice as expensive as a similar board from Ali / Ebay” goes all the way down to the basic component level. I hope you can see that I am working on addressing that. I would be interested in what other small manufacturers in America (and in other countries besides China) do. Should I just start sourcing more components from China? Should I be using smaller distributors in the US? (I am skeptical that would make a big difference because of my understanding that manufacturers are basically setting the prices). Or is there something else I’m completely missing? I know some of you who read my posts work for the electronics manufacturers and distributors; can you help push for getting better component pricing in the US? For all of you who like making electronics, wouldn’t it be nice to have the option (or for your kids to have the option) to do that without having to live in China or being limited to industries like aerospace and military where components costs might not matter as much?

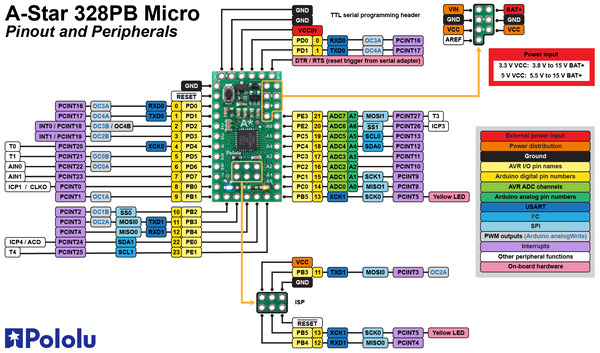

New product: A-Star 328PB Micro

Today we are releasing our newest A-Star programmable controller, the A-Star 328PB Micro. It is basically our version of the ubiquitous Arduino Pro Mini type products, but with the newer ATmega328PB microcontroller. The board itself is pretty straightforward (though the updated AVR is exciting), so the main thing I want to share in this post is our history with the Atmel ATmega328PB microcontrollers (this was before Microchip acquired Atmel) and how this product would not have existed without our lower-cost manufacturing initiative that I have been discussing.

We have been using the ATmega8, and then the ATmega48, ATmega168, and ATmega328P, since 2004 in many of our user-programmable products because of their versatility and excellent free compiler support (which also made Arduino possible). We first heard about the ATmega328PB in early 2014. The product kept being delayed, and I did not get a quote for them until October 2015. I ordered a reel right away; it arrived in March 2016. Over those two years, we put our AVR-related efforts into the ATmega32U4, releasing several A-Star 32U4 programmable controllers and using it on robots like the Zumo 32U4. The ATmega32U4 was a superior part with native USB and more I/O lines, making it a better fit for many of our applications. By the time we finally got the ATmega328PB parts, we had the A-Star 32U4 Micro available for just $12.75, making it less exciting to put effort into a lower-performance product that might end up costing almost the same amount.

|

Original ATmega168-based Baby Orangutan robot controller from 2005 (left) next to A-Star 32U4 Micro boards. |

|---|

The new manufacturing equipment I ordered in the fall of 2017, along with the availability of our latest AVR programmer, brought attention back to the feasibility of a basic ATmega328PB carrier. I was hesitant to put effort into a product where we could not offer something substantially more compelling than what was already available. Despite the ATmega328PB being out in the wild for almost two years, it still had not really made it into many Arduino products, so I thought that perhaps we could offer something there. But more importantly, I wanted to see how low we could price it. I was aware of Arduino Pro Mini clones available on eBay and the AliExpress-type sites for under $3. Most official Arduino Pro Mini type products cost more like $10. For this project to be worthwhile, I wanted to get under $5.

It turns out we had to squeeze quite a bit just to get to the upper limit of that “under $5” goal, and so we are releasing this product at a unit retail price of $4.95. It’s not the under-$3 you can find for the absolute cheapest clones, but if you get the A-Star 328PB Micro from us, you are getting a well-supported, well-made product (each unit is 100% automatically visually inspected and 100% functionally tested) and supporting a company that is doing more than just copying products that are already out there.

It is my hope that by being able to offer the A-Star 328PB Micro for under $5, we are offering something meaningful, giving you a new option for general-purpose controllers at the price of a cheap lunch. I am interested to hear what you think. Is the 328PB interesting when you can get USB for not much more? Is the price low enough for you to buy from us instead of getting it from China?

We are offering the A-Star 328PB Micro in four voltage and frequency combinations:

- 5 V, 16 MHz (blue power LED)

- 5 V, 20 MHz (red power LED) Note: See item-specific page for speed warning.

- 3.3 V, 8 MHz (green power LED)

- 3.3 V, 12 MHz (yellow power LED)

|

A-Star 328PB Micro pinout diagram. |

|---|

The A-Star 328PB Micro provides access to all 24 I/O lines of the microcontroller and ships with an Arduino-compatible serial bootloader; you can also use an AVR in-system programmer (ISP) for access to the entire chip. We recommend our USB AVR Programmer v2, which supports both programming interfaces and can be configured to run at either 3.3 V or 5 V.

Last but not least, we are continuing our plan of offering new products at the highest quantity price break at single unit quantities as an introductory celebration. That means that for the first 100 customers, you can get an A-Star 328PB Micro for just $3.87! (Must use coupon code AS328PBINTRO; click to add the coupon code to your cart.)

While we assemble (and design and document and ship and support) the boards here in Las Vegas, we still get the bare PC boards from China, where they are currently on holiday celebrating Chinese New Year. That is constraining how many units we can make at the moment, so we are limiting shipments to 5 units per customer. However, the introductory coupon has no quantity limit, and you can order more than five at that price if you would like. Backordered units are likely to ship within a few weeks.

How I picked our new machines (and what they mean for you!)

|

The new equipment I have been sharing for the past two weeks (here and here) represents our biggest manufacturing capacity increase in five years. Today I will go into more detail about the pick and place machine and stencil printer we got, along with what it means for our customers.

Assembling a circuit board with surface-mounted components involves three main steps: printing solder paste on a bare circuit board, placing the components on the board, and then sending the board through an oven, which melts the solder paste, soldering the components to the board. You can see the steps in this video we made a while ago about how the A-Star 32U4 Micro gets made:

Pick and place machine

At the end of 2012, we got two very different pick and place machines, an SM421F from Samsung (which has since sold their electronics assembly equipment business to Hanwha) and an iineo from Europlacer. Both machines are very versatile, designed to place everything from the smallest components to large and tall parts, and we have run all of our products on both machines. I got both machines back then because each manufacturer made a compelling case, and I wanted to try both. The new machine we installed this month is another Europlacer machine. So… does that mean it’s better?

First off, the Europlacer machine is much bigger and more expensive than the Samsung/Hanwha machines, so the real comparison for this round of new equipment was two Hanwha machines vs. one from Europlacer. Each SM482 Plus has 120 feeder slots, so two of those machines have very similar feeder capacity to the 264 slots of the iineo+. The pair of Hanwha machines is also similar to the Europlacer option in terms of combined size and price. I should also say that we have had a great experience with both machines and vendors, and I do not regret having bought either of those machines in 2012. The Hanwha machine route had one major advantage: the machines, even individually, are faster than the Europlacer in the straight parts per hour component placement rate; with two of them, it should be no contest, with a combined advertised placement rate of around 60,000 components per hour vs. around 15,000 for the Europlacer machine. Having two smaller machines would also give us some more flexibility (we could operate them as two separate machines, running different products, as opposed to one big machine) and redundancy, so that we could keep at least some production running if one machine went down. The redundancy argument probably would have pushed me in the direction of the Hanwha, two-machine route, if we didn’t already have any other machines.

|

But we did already have a Europlacer machine, so getting a second one would give us that redundancy. And despite the sustained placement rate being four times lower, we expect the Europlacer to actually be the faster option for our purposes. That’s because our products tend to be relatively small and simple, but we have hundreds of different products (and I want it to be thousands soon), so we need to be able to run many different products a day efficiently. We might get some of that efficiency from the Europlacer software, though it’s not that clear to me that there really is that much difference between the machines (as opposed to operator familiarity). The interchangeable carts should also help eventually, though I do not expect that to make much of an impact until we have more of them, and so far we just have enough to basically fill each machine. What I think matters the most is the huge feeder count on a single machine, minimizing the amount of component changes that have to be made from one product to the next. It’s inevitable that the raw throughput will be lower when the placement head has to on average travel farther from the board being assembled to the part in the machine, but for our mix of quantities, it’s worth it.

|

132 feeder locations across four carts on the back side of the Europlacer iineo+ machine. There are 132 more on the other side! |

|---|

Stencil printer

For solder paste printing, I thought some more about a jet printer. The general idea is that the printer has the solder paste in a cartridge that moves all over the bare circuit board and squirts some on every pad, as opposed to squeegeeing a bead of solder paste through a stencil the way solder paste is more typically applied. I have been looking at MyData’s jet printers since they came out probably over ten years ago now, and the prospect of not needing stencils and being able to vary deposit thicknesses keeps being attractive, especially for our scenario where I want to be able to do just a few panels each of many different designs every day. But, at more than double the cost of a traditional stencil printer, the cost seems difficult to justify, especially since we cut our own stencils in-house. So, I ended up ordering another stencil printer from Europlacer since we are happy with the one we already have. MyData is now Mycronic, and you can see more about their jet printer at the Mycronic Jet Printer page.

|

The technician from Europlacer performing the installations was disappointed that we were pairing the nice new color-coordinated stencil printer with our Samsung pick and place machine. |

|---|

Commitment to better manufacturing and lower prices

What does all this mean for our customers? (Other than a higher likelihood of getting to see an awesome machine running when you come visit us.) Partly I am sharing this because I expect most of you like making things, like to see how things get made, and would love to have machines like this of your own. More importantly, I want to remind you of the effort we are going through to bring you better products at lower prices. Having more of this extremely flexible manufacturing capacity means we can keep churning out new prototypes quickly and then be able to manufacture the products at a globally competitive price. Over the coming months, we will be assessing our manufacturing costs and lowering prices on many of our popular products, and new products will have lower prices as soon as we introduce them.

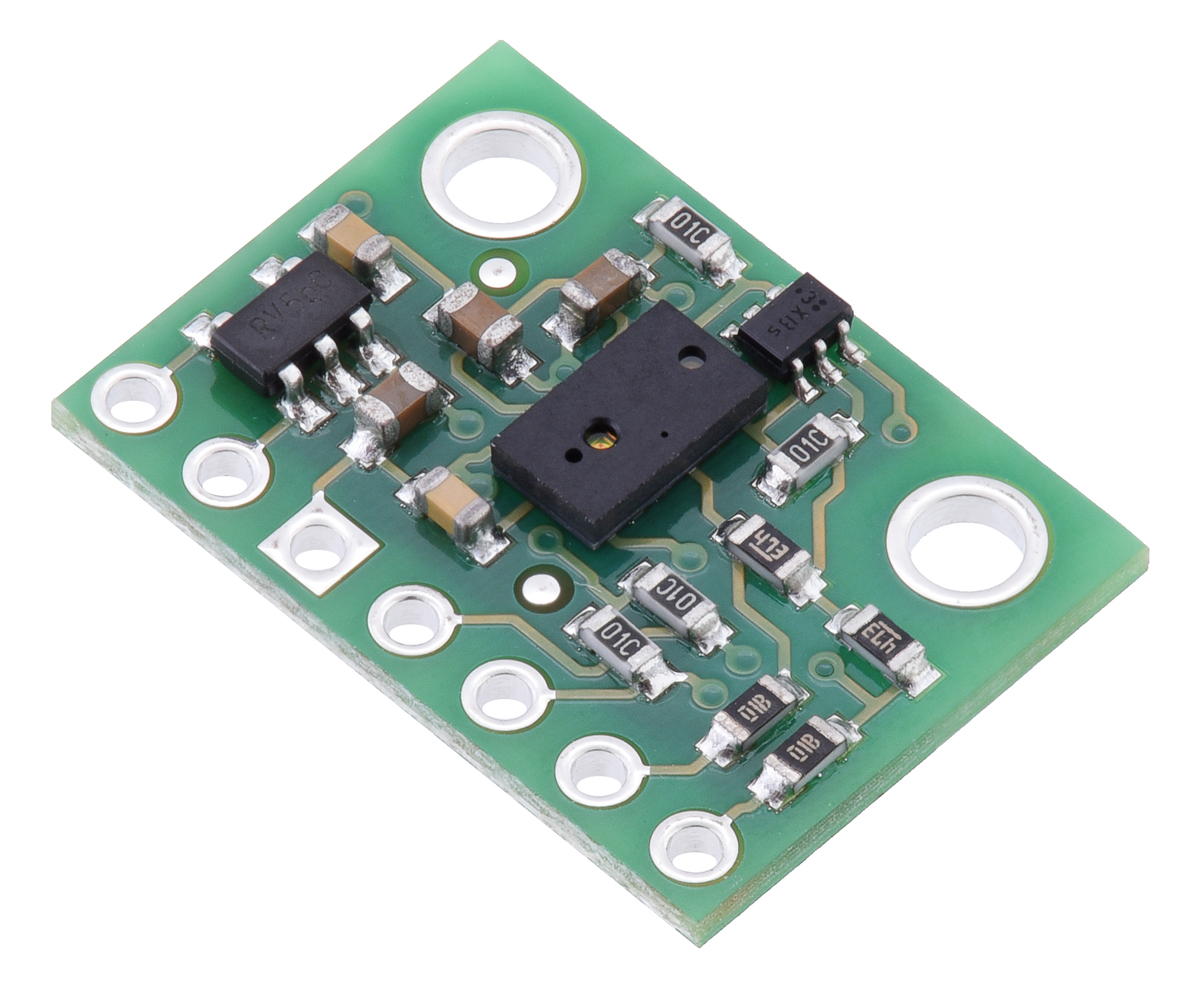

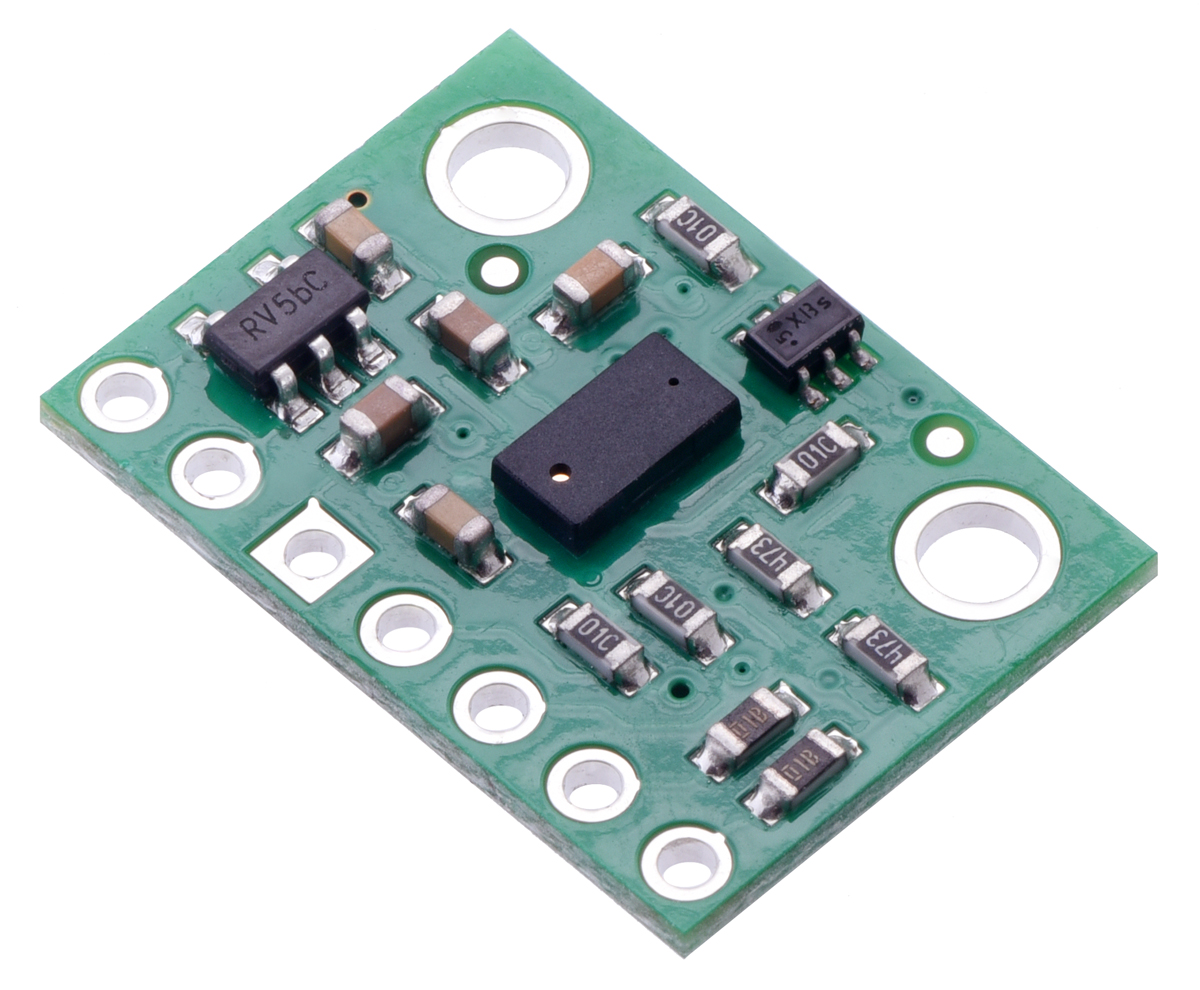

We are kicking that off with a substantial price cut on our popular time of flight distance sensors:

|

|

| VL6180X Time-of-Flight Distance Sensor Carrier with Voltage Regulator, 60cm max |

VL53L0X Time-of-Flight Distance Sensor Carrier with Voltage Regulator, 200cm Max |

And to help everyone share in our excitement, we’re offering the new, low, 100-piece pricing at single-unit quantities to the first 100 customers using coupon codes 2489PRICECUT and 2490PRICECUT (Click to add both coupon codes to your cart).

Free USA shipping on hundreds of Pololu metal gearmotors

Since my last post about free shipping in the USA, we expanded the program to include orders consisting of $40 or more in free add-on shipping items. And today, we added almost 300 different metal gearmotors to our selection of products that ship for free in the USA. (Don’t worry, we don’t pile up actual good production motors like we did in that picture; those were returned by an infamous, once-skyrocketing startup.)